This article was first published in The Structural Engineer on 2 February 2026.

Andy Yates suggests behavioural science models offer a framework to enable engineers to shift mindsets towards a reuse-first approach.

Introduction

For decades, the construction industry appears to have operated on a deeply embedded assumption that when a building reaches the end of its useful life, we demolish it and build new. This business-as-usual approach is so established that it often escapes scrutiny. Yet we probably all acknowledge, deep down that this model is environmentally and ethically unsustainable.

We continue to waste far too much. The construction industry has made hardly any progress in reducing waste and while recycling and recovery options are developing, they are not the answer to the huge quantities of materials and energy which the industry continues to use.

Demolition often discards perfectly serviceable structures and materials along with enormous quantities of embodied carbon, social utility, and engineering ingenuity. And this happens even though, as structural engineers, we have the knowledge and tools to retain, repair, adapt and reuse what we already have. The problem is not technical capacity, rather that we and the industry frequently have the wrong mindset.

We treat historic buildings with care, undertaking conservation works to repair, retain and preserve these assets. But when it comes to the more ordinary, everyday buildings and infrastructure, we appear to default to demolition, discarding the majority of the embedded value of the materials, and then using a whole load of new resources to build again.

We already have the skills to analyse existing structures, understand their behaviour, and adapt them to new uses. Techniques such as load assessments, materials testing, non-destructive testing and investigations, repair techniques, strengthening, and so on are mature and well understood. In many cases, reuse is the lower-carbon, quicker and cheaper solution but too often it is dismissed before it is even explored.

If the profession is to help meet climate goals and reduce the material intensity of construction, then a fundamental shift is required. Reuse must become the norm and the default option, while new build becomes the carefully justified exception. Achieving this requires a cultural and behavioural transformation amongst engineers but also the clients, architects, contractors, and stakeholders we work with.

Behavioural change

The demolition-first approach remains dominant because it is familiar, perceived as low-risk, and embedded in industry norms. Clients are often advised that reuse is complex or expensive, even when evidence suggests the opposite. Engineers sometimes assume that adapting a structure introduces uncertainty. Contractors may have greater commercial certainty in new build. In reality, many of these are perceptions rather than realities. To shift these entrenched assumptions, it helps to understand the mechanisms of behavioural change.

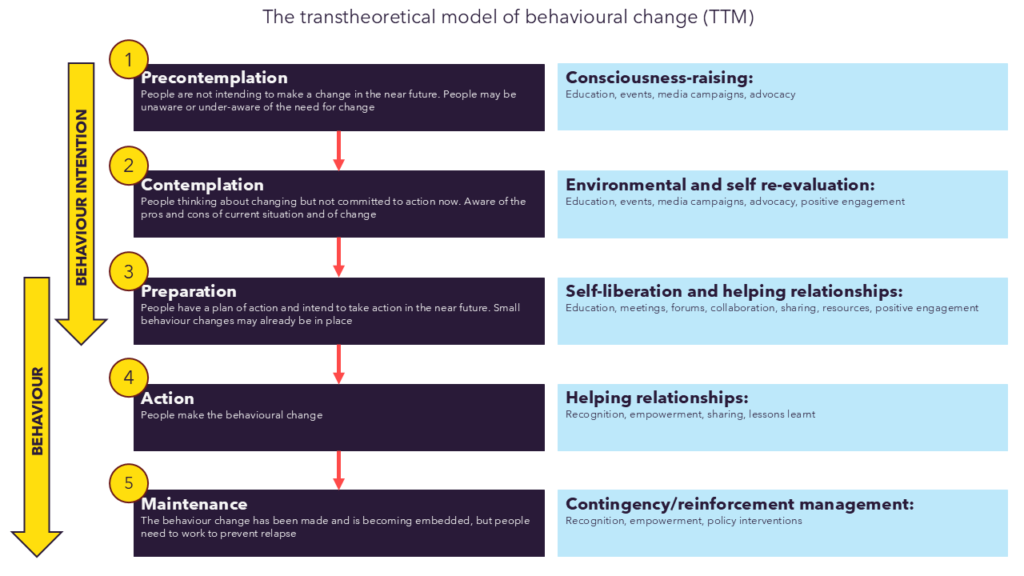

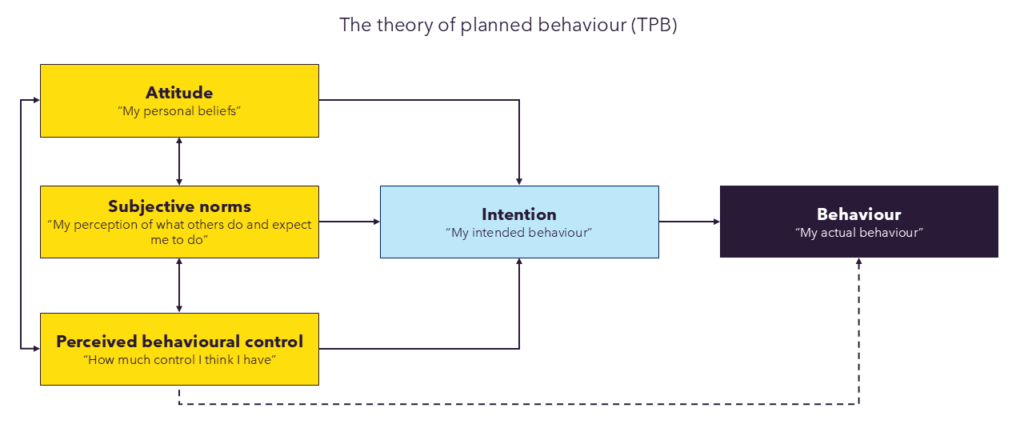

Behavioural science offers two widely used frameworks, the Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change (TTM) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), that can help explain why change is slow, and what we can do to accelerate it.

Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change

The Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change (TTM) describes five stages through which individuals as well as the industry progress when adopting new behaviours. Originally developed for public health, TTM maps how people move from ‘not considering change’ to ‘sustained new behaviours’. These stages apply remarkably well to the cultural shift required in construction. Applying TTM to reuse provides a framework for understanding and accelerating change.

1. Precontemplation: ‘Demolition is normal.’

At this stage, stakeholders do not yet recognise the need for change. Demolition is seen as standard practice and reuse as niche.

Our task: raise awareness using data, case studies, compelling examples, embodied-carbon comparisons, and success stories to show what is possible.

2. Contemplation: ‘Reuse might be beneficial, but…’

Stakeholders are open to the idea but unsure. Concerns about risk, cost, programme or aesthetics dominate.

Our task: reduce perceived barriers and counter misconceptions with evidence, explain processes clearly, and reframe reuse as opportunity-driven rather than constraint-driven.

3. Preparation: ‘We want to try reuse.’

Teams are willing but need guidance.

Our task: provide clear methodologies, share guidance, and embed reuse pathways into design processes, scopes, and contracts.

4. Action: ‘We are reusing.’

Projects begin to incorporate retention and reuse of structures.

Our task: document successes, celebrate these projects, share lessons learned, and reinforce the benefits realised. Demonstrate the professional pride and engineering creativity that reuse can unlock.

5. Maintenance: ‘Reuse is the default.’

The ultimate goal: cultural normalisation. Demolition becomes a last resort requiring justification.

Our task: reinforce and normalise the behaviour, embed reuse into guidance, update standards, shift procurement processes, and educate so it remains the norm.

TTM shows us that change is a journey. Different stakeholders sit at different stages and our responsibility is to help them progress towards making reuse the expected approach. Understanding where different stakeholders are on the journey is also beneficial to understand what our role should be at each stage.

Theory of planned behaviour

While TTM describes stages, the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) explains why people decide to adopt (or reject) a behaviour. TPB argues that behaviour is shaped by three factors.

1. Attitude:

Do people think reuse is positive? Does it align with their values?

– For engineers, this means demonstrating that reuse is not a compromise, rather it is an expression of professional creativity, carbon literacy, and engineering rigour.

2. Subjective Norms:

Do people think others expect them to reuse?

– Industry norms are incredibly powerful. If clients perceive that ‘everyone else is building new’, they frequently follow. Conversely, if leading firms, public bodies and major developers consistently prioritise reuse, expectations will shift.

– Engineers can influence norms by championing reuse in throughout project stages, but especially in early-stage briefing developments, structural assessments and concept design.

3. Perceived Behavioural Control:

Do people feel capable of delivering reuse successfully?

– This is often the biggest hurdle. Stakeholders may believe that the process is technically complex or risky.

– Engineers can counter this by simplifying early assessment, clearly communicating uncertainty, offering strategic advice from the outset, and demonstrating that the industry already has the competence needed.

TPB reveals that intent-to-reuse alone is not enough. To embed reuse as normal practice, we must shift attitudes, reshape norms, and increase confidence.

Reshaping expectations

The Engineers Reuse Collective exists to demonstrate, champion and advocate for greater reuse across the industry. By recognising the behavioural changes required, we equip our members and the wider industry with the confidence, evidence and leadership to implement and accelerate that change.

Structural engineers often sit at the early stages and therefore the most influential point of a project’s life. We have the authority, and increasingly the obligation, to challenge assumptions and reshape expectations. We need to be saying, ‘Let us look first at what we already have’, and ‘What can we keep?’. We need to demonstrate that reuse is not a compromise, it is ingenuity, responsibility, and progress.

But engineers cannot do this alone. We must influence the mindsets of clients, architects, contractors, and other stakeholders. Nearly every obstacle to reuse – perceived risk, uncertainty, cost assumptions – is ultimately behavioural rather than technical.

The climate emergency demands more than improved efficiency. It requires a fundamental reduction in material use, and that means retaining and reusing what we already have. We have the technical solutions. We have the tools. What we need now is a transformation in mindset.

By applying behavioural science to our own profession, we can recognise that the biggest barriers are not technical, they are psychological and cultural. Through the lenses of the Transtheoretical Model and the Theory of Planned Behaviour, it is clear that we must change our mindsets, and help others change theirs, so that reuse becomes the default and new build the outdated exception.

Andy Yates is Director of The Engineers Reuse Collective.