Introduction

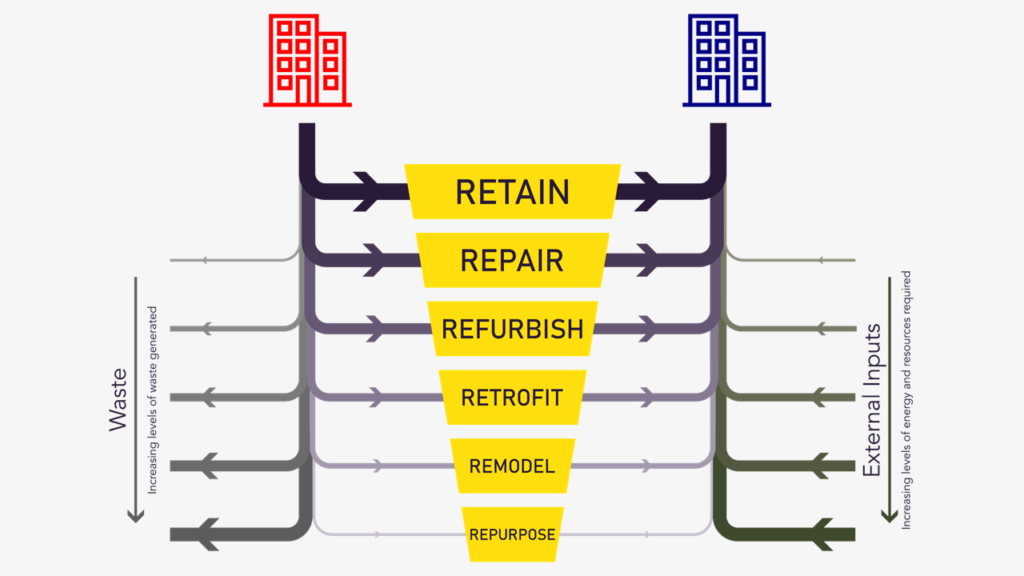

As structural engineers, we have a pivotal role in reducing embodied carbon in the built environment [1] [2]. The Reuse Hierarchy presented here provides a clear, evidence-based framework for decision-making, prioritising retention, repair, and refurbishment of existing structures over more invasive and disruptive interventions. Towards the top of the hierarchy, reduced levels of waste, and reduced external inputs of energy and materials leads to lower embodied carbon. As interventions move further down the hierarchy, waste, material use, and carbon intensity increase. By applying this hierarchy, engineers can maximise the value of existing assets, minimise environmental impact, and align our projects to whole-life carbon and circular economy principles.

Background

Structural engineers play a decisive role in shaping the material and carbon outcomes of the built environment. The primary structure is typically the single largest contributor to a building’s embodied carbon [3], yet it is also the element with the greatest capacity for longevity, adaptation, and continued use. Decisions taken by structural engineers therefore have significant influence on whether value is conserved or discarded.

As structural engineers we must prioritise reuse because the construction sector is a major contributor to embodied carbon and material waste. In the UK, over 60% of waste generated comes from the construction, demolition and excavation sector [4]. Every asset and component reused reduces the need for new materials, cutting both energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Beyond environmental benefits, reuse also preserves the value of existing assets, minimises landfill, and encourages innovation in design for adaptability. With growing regulatory and societal pressure to decarbonise infrastructure, engineers have a professional and ethical responsibility to embed reuse into their practice, moving away from a default ‘demolish and rebuild’ approach.

We should resist demolition wherever practicable and embed retention and reuse, in some form, as a fundamental consideration in every design, while confirming through whole-life carbon assessment that it genuinely represents the lower-carbon option [5].

The Reuse Hierarchy provides a clear and logical framework for these decisions. Applied as a priority order, it seeks to maintain structural assets and components at their highest possible value, while minimising waste and the need for additional external inputs of energy and materials. Crucially, as one moves down the hierarchy, both waste generation and embodied carbon emissions increase.

The hierarchy can be applied at both an overall asset level, as well as to the various structural items which make up the asset (e.g. foundations, superstructure, secondary steelwork etc.). In each case, preference should be given to the highest level of the hierarchy.

The Reuse Hierarchy

The Reuse Hierarchy is defined as follows:

- Retain

- Repair

- Refurbish

- Retrofit

- Remodel

- Repurpose

Each step down represents a reduction in retained structural value and a corresponding increase in intervention, material demand, and carbon impact.

Retain: The Structural Default

Retention sits at the top of the hierarchy because it preserves almost all embodied value. Retaining existing frames, slabs, foundations, and loadbearing elements avoids demolition waste, new material production, and energy-intensive construction processes.

Multiple industry studies show that the substructure and superstructure typically account for 50–70% of a building’s upfront embodied carbon (A1–A5), depending on typology and material choice [6] [7]. As a result, retaining the primary structure is consistently identified as the most effective strategy for reducing embodied carbon.

Retention is not passive. It requires investigation, testing, and reassessment, often using modern analysis methods that were unavailable at the time of original design. However, the carbon cost of these activities is negligible compared with the emissions associated with concrete production, steel fabrication, demolition, and waste processing.

Repair: Low-Carbon Life Extension

Repair addresses localised deterioration while retaining the vast majority of the original structure. Typical interventions include concrete repair, corrosion mitigation, strengthening of isolated elements, and protective treatments.

Repair interventions generally carry an order of magnitude lower embodied carbon than replacement of equivalent structural elements and are a key mechanism for extending service life with minimal environmental impact.

For structural engineers, repair demands rigorous diagnosis and durability design, but from a whole-life carbon perspective it remains one of the most efficient interventions available.

Refurbish: Retaining the Carbon-Intensive Frame

Refurbishment typically involves retention of the primary structural frame while upgrading secondary elements. This approach preserves the most carbon-intensive components of the building, particularly reinforced concrete and steel frames.

Whole-life carbon studies show that frame retention can significantly reduce upfront embodied carbon when compared with full demolition and rebuild, even where significant non-structural replacement is undertaken [3].

However, these savings are highly sensitive to structural decisions. Conservative assumptions leading to unnecessary strengthening or replacement can rapidly erode the carbon benefits of refurbishment.

Retrofit: Carbon Trade-Offs Must Be Explicit

Retrofit involves performance-driven interventions directed at improving operational energy, resilience, or regulatory compliance, rather than changes driven by structural necessity. Interventions may range from light upgrades, to deeper measures that introduce new services or environmental performance enhancements. For structural engineers, retrofit can include localised structural modifications or strengthening while retaining the majority of the primary structural elements.

While retrofit can deliver substantial operational carbon savings, it often introduces higher upfront embodied carbon due to additional materials and construction processes.

Both PAS 2080: 2023 [8] and the UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard [9] emphasise the importance of whole-life carbon assessment, warning against interventions that reduce operational emissions at the expense of upfront carbon impacts. Structural engineers have a responsibility to quantify and communicate these trade-offs clearly.

Remodel: Increasing Intervention, Increasing Impact

Remodelling involves significant structural alteration, including removal of loadbearing elements and introduction of new structural systems. At this level, demolition arisings increase substantially, as do temporary works, construction energy, and new material inputs.

Embodied carbon assessments show that once major structural components are removed or replaced, the upfront carbon profile begins to approach that of new construction, even where parts of the original structure are retained.

While remodelling may still offer carbon benefits relative to full demolition, it represents a clear step down the reuse hierarchy and should be justified accordingly.

Repurpose: The Highest Carbon Reuse Option

Repurposing involves adapting a structure or components for a fundamentally different use, often requiring extensive modification or reworking. To repurpose structures and structural components typically requires a significant amount of external inputs and generates higher levels of waste than other forms of reuse higher up the hierarchy.

This reinforces the positioning of repurposing at the bottom of the reuse hierarchy. Although still preferable to demolition, it should only be explored once higher-value options – retention, repair, and refurbishment – have been fully explored and discounted.

At present, there is limited repurposing of structural components being implemented in practice. Issues around supply chains, commercial viability, testing, certification and warranties, amongst others, are hampering the take up of this form of reuse.

However, there are an increasing number of research projects, prototypes and demonstrator projects being undertaken which will hopefully improve the viability of repurposing.

Case Studies

The six short case studies that follow illustrate each of the reuse typologies on the hierarchy (Retain > Repair> Refurbish > Retrofit > Remodel > Repurpose). As is often the case in real world projects there is overlap between the differing typologies of reuse, but these examples clearly demonstrate how reuse has been successfully incorporated.

- Retain – Hay Castle

- Repair – Bradford Live

- Refurbish – Kinning Park Complex

- Retrofit – Neighbourhood North

- Remodel – Selfridges, Duke Street

- Repurpose – Rafter Walk

Conclusion

The Reuse Hierarchy reinforces a fundamental principle for structural engineers: as we move down the hierarchy, waste increases, external inputs increase, and embodied carbon rises. No amount of optimisation in new construction can match the carbon savings achieved by retaining existing structures.

In a carbon-constrained future, structural engineering excellence must include stewardship of existing assets as a core competency. The reuse hierarchy provides a clear, evidence-based framework for delivering that responsibility.

References

- Arnold, W. (2020). ‘The structural engineer’s responsibility in this climate emergency’. The Structural Engineer, Volume 98, Issue 6, 2020, Page(s) 2. https://doi.org/10.56330/SDZM2461

- Gowler, P. et al. (2023). ‘Circular economy and reuse: guidance for designers’. London. IStructE Ltd.

- Collings, D. (2020). ‘Carbon footprint benchmarking data for buildings’. The Structural Engineer, Volume 98, Issue 11, 2020, Page(s) 4. https://doi.org/10.56330/TFOG9016

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, (2025), ‘UK statistics on waste’. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-waste-data/uk-statistics-on-waste

- Gibbons, O., Orr, J., and Arnold, W. (2025). ‘How to calculate embodied carbon (3rd edition), London. IStructE Ltd. Available from https://www.istructe.org/resources/guidance/how-to-calculate-embodied-carbon/

- Arup et al. (2021). ‘Net-zero buildings. Where do we stand?’ World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Available from https://www.wbcsd.org/resources/net-zero-buildings-where-do-we-stand/.

- Szalay, Z. (2024). ‘A parametric approach for developing embodied environmental benchmark values for buildings’. Int J Life Cycle Assess Vol. 29, 1563–1581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-024-02322-w.

- British Standards Institution (2023). ‘Carbon Management in Buildings and Infrastructure – PAS 2080: 2023’. London, British Standard Institution. Available from https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/insights-and-media/insights/brochures/carbon-management-in-buildings-and-infrastructure/.

- Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard Limited (2025). ‘UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard, Pilot Version rev2’. Available from https://www.nzcbuildings.co.uk/_files/ugd/6ea7ba_55a9d021ca274eda8fbf7b07c70e70cb.pdf